Ribiera Sacra

Introduction

They call the north west of Spain "Green Spain". It rains a lot

and it is indeed very green and fertile.

The two geographical features that influence the climate of this corner of Spain are the Cordillera Cantabrica and the proximity of the Atlantic Ocean. The Cordillera is a massive chain of mountains, running about 300 km across the north of Spain, almost parallel to the Bay of Biscay. It also extends to the south-west as the Sierra de Ancares which forms the boundary between Galicia and Léon.

Winds from the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic bring rain to the coast, to the mountain slopes and to the hilly lands between the coast and the mountains. The coastline is windy and rugged, along the Galician shores characterised either by rocky cliffs or a series of rias, submerged valleys where the sea extends many kilometres inland.

The two geographical features that influence the climate of this corner of Spain are the Cordillera Cantabrica and the proximity of the Atlantic Ocean. The Cordillera is a massive chain of mountains, running about 300 km across the north of Spain, almost parallel to the Bay of Biscay. It also extends to the south-west as the Sierra de Ancares which forms the boundary between Galicia and Léon.

Winds from the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic bring rain to the coast, to the mountain slopes and to the hilly lands between the coast and the mountains. The coastline is windy and rugged, along the Galician shores characterised either by rocky cliffs or a series of rias, submerged valleys where the sea extends many kilometres inland.

Much of the good walking is in the mountain areas. The

dramatic coast and adjacent countryside are also accessible

by a range of routes, either the limited number of long distance

trails that cross the area or many local shorter sendieros.

We have visited this area twice. The first time was in the early summer of 2003 after our circuit of northern Portugal when we came, at last, to Santiago de Compostella and then briefly explored the Picos de Europa. It rained a lot but we loved the area so much that we asked the locals when we should visit to find more reliable weather. They said to come in September, so we did - the very next year.

Starting and ending in Bilbao, our route in 2004 was an anti clockwise loop, first along the coast then inland to the mountains, exploring the relatively unknown Ancares and Somiedo national parks and finally spending two weeks in the Picos de Europa. It only rained a bit.

We have visited this area twice. The first time was in the early summer of 2003 after our circuit of northern Portugal when we came, at last, to Santiago de Compostella and then briefly explored the Picos de Europa. It rained a lot but we loved the area so much that we asked the locals when we should visit to find more reliable weather. They said to come in September, so we did - the very next year.

Starting and ending in Bilbao, our route in 2004 was an anti clockwise loop, first along the coast then inland to the mountains, exploring the relatively unknown Ancares and Somiedo national parks and finally spending two weeks in the Picos de Europa. It only rained a bit.

Bilbao and Gernika

You go to Bilbao, in the Basque country, because because it is an easy

entry point to northern Spain and because of the Guggenheim Museum.

The Casco Viejo, or old town, is less well known than the Guggenheim

but is lively with restaurants, bars and shops and is well located on the

Norman Foster designed metro. It is a good place to stay.

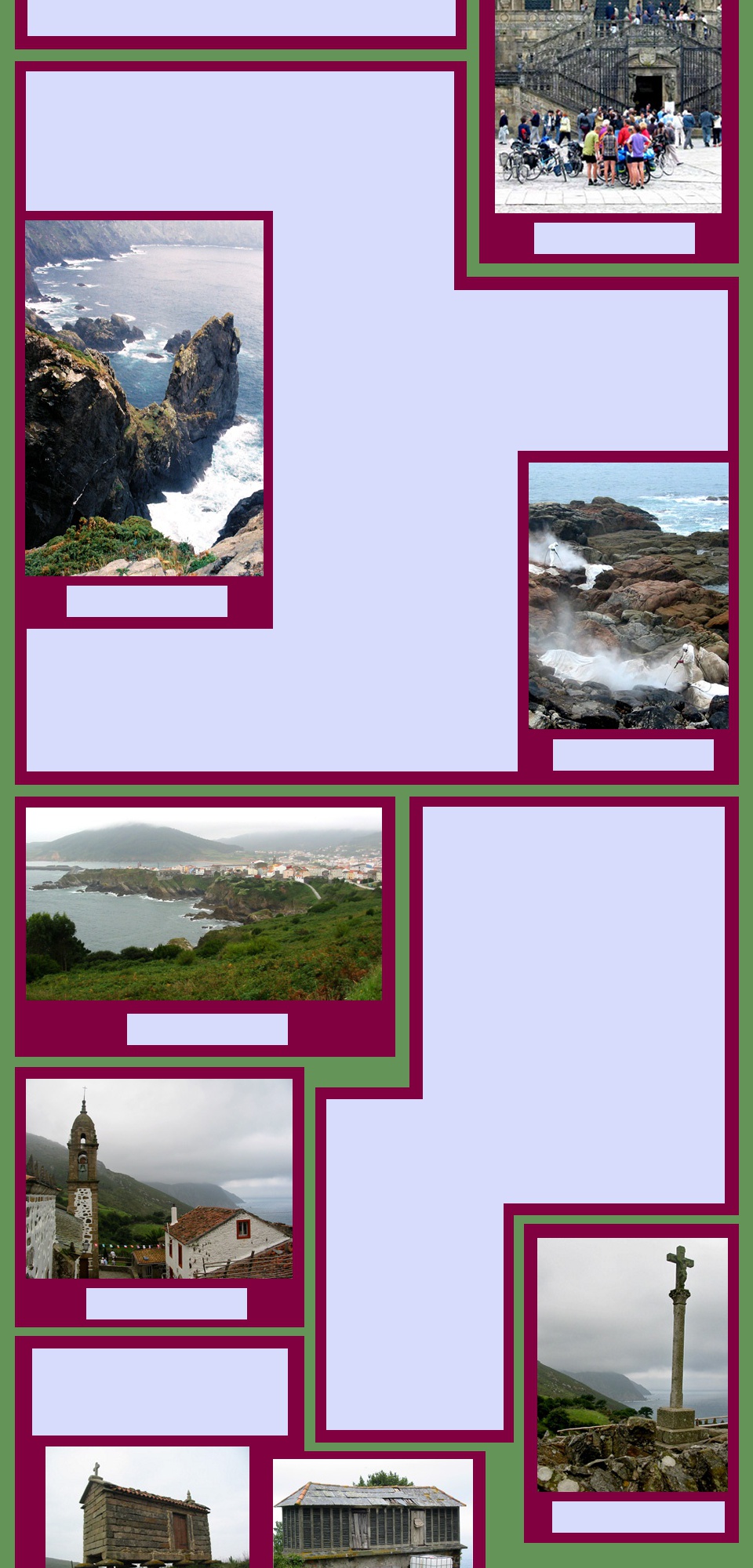

The Frank Gehry designed Guggenheim Museum was opened in 1997 and has drawn hosts of visitors ever since. It is a fantastic structure of titanium and glass, designed to resemble fish scales. Inside, light pours into the lofty spaces which can accommodate very grand scale exhibits. The permanent exhibits do not have the drawcards found in the world's major museums but there are always interesting temporary exhibitions and we were lucky enough to discover a major exhibition of Alexander Caldor's fascinating mobiles.

The Frank Gehry designed Guggenheim Museum was opened in 1997 and has drawn hosts of visitors ever since. It is a fantastic structure of titanium and glass, designed to resemble fish scales. Inside, light pours into the lofty spaces which can accommodate very grand scale exhibits. The permanent exhibits do not have the drawcards found in the world's major museums but there are always interesting temporary exhibitions and we were lucky enough to discover a major exhibition of Alexander Caldor's fascinating mobiles.

A short train trip from

Bilbao is Gernika, grimly

remembered because of

the bombing of the city

in 1937. It is a quiet

place today, going about

its business without a

great deal of interest

from outside. An

excellent little museum

has many photos and

Gernika

models and a very moving film is shown, simulating the nightmarish events of the day

when German planes dropped bombs on a crowded market place. In the town itself

there is a full size mosaic of Picasso's great painting.

Galicia - Santiago de Compostella

and the Coast

Santiago de Compostella

In Galicia, the pilgrim routes coming from all directions converge on Santiago de

Compostella. The pilgrimage to Santiago, el camino, has become an amazing

phenomen with the number of pilgrims reaching the Cathedral of Santiago growing

enormously over the years. The peak was reached in 2010, a holy year, when 272,135

pilgrims received their certificado. The following year 2011, there was some respite with

only 183,366 arriving. In 1988, when we did our stage between Le Puy and Conques in

France (link) only 3,501 completed the journey. It has become a craze, a symbol of "self

discovery", almost a cult, but most of all a huge business.

We have visited Santiago twice and somewhat defiantly, never arrived on foot. The first time we came by train from Portugal and the second time drove our hire car into the enormous car park that has been excavated under the town. Notwithstanding the number of visitors, Santiago is a charming and agreeable town - or at least it was when we visited before the extraordinary increase in pilgrims. The historic centre is a maze of narrow pedestrianised streets, colonnaded buildings lining the streets are of dark stone with white window frames and trimmings and under the colonnades are little shops selling souvenirs to commemorate the pilgrims' arrival. This has probably not changed over the centuries. A unique feature that we loved was the diversity of lead drainpipes decorated with pretty designs and curious little people.

We have visited Santiago twice and somewhat defiantly, never arrived on foot. The first time we came by train from Portugal and the second time drove our hire car into the enormous car park that has been excavated under the town. Notwithstanding the number of visitors, Santiago is a charming and agreeable town - or at least it was when we visited before the extraordinary increase in pilgrims. The historic centre is a maze of narrow pedestrianised streets, colonnaded buildings lining the streets are of dark stone with white window frames and trimmings and under the colonnades are little shops selling souvenirs to commemorate the pilgrims' arrival. This has probably not changed over the centuries. A unique feature that we loved was the diversity of lead drainpipes decorated with pretty designs and curious little people.

There are many good restaurants

with a fantastic range of tapas

and raciones which were a joy to

us after the heavy food of

Portugal. Among the souvenir

shops are jewellery shops which

sell quite elegant jewellery made

from silver and jet - a tasteful

souvenir of Santiago which may

be preferred to cockle shells.

But of course, we have all come

here to see the cathedral which

reveals itself almost by chance.

Out of the narrow streets of the

town you suddenly emerge into the enormous Praza do Obradoiro to be confronted by one

of the most elaborate Baroque facades in Christendom. It was undoubtedly a lot simpler at

the time of its construction between 1075 and 1211 but now it goes for the full-on baroque

WOW factor.

The pilgrims arrive in the Praza in jubilation and tearful exhaustion. It is very emotional to be there to see the arrivals - on foot or bicycle - and to reflect that this scene has played out for ten centuries or more.

The pilgrims arrive in the Praza in jubilation and tearful exhaustion. It is very emotional to be there to see the arrivals - on foot or bicycle - and to reflect that this scene has played out for ten centuries or more.

La Costa da Morte

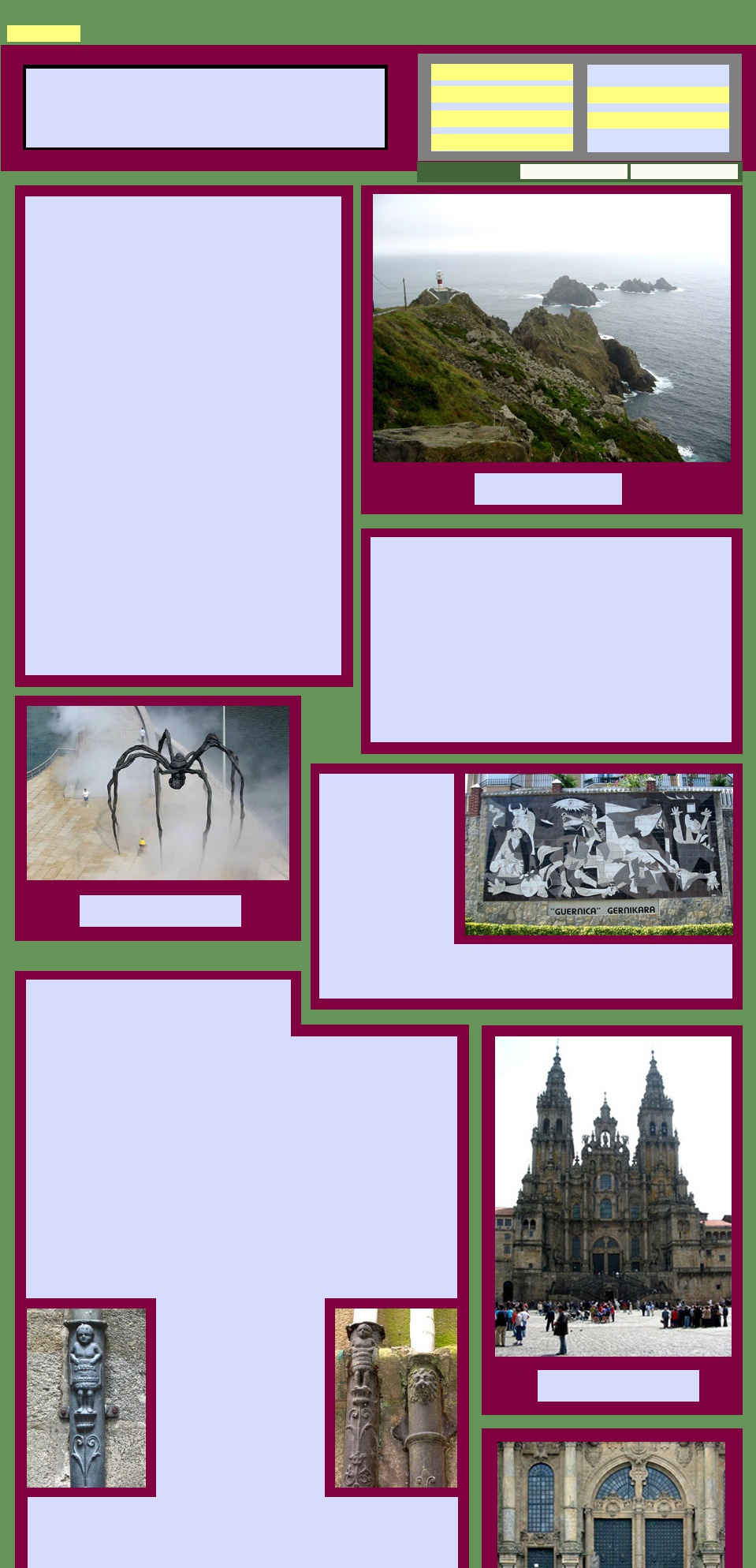

For many pilgrims the journey continues to Cabo Fisterra, Finisterre in English, a rocky

peninsula 90 km from Santiago, and almost the westernmost point of the Iberian

Peninsula. Those that continue to the cabo burn their clothes or boots there to mark the

very end of the pilgrimage. The origin of this recent tradition is unclear.

Fisterra enjoys a kind of mythical status as being at the "edge of the world". The name Fisterra comes from Latin 'finis terrae', literally 'end of land'. Mistranslations like 'the end of the earth' or 'the end of the world' contribute to the mythology. Cap Finisterre in Brittany and Landsend in Cornwall are similar 'ends of the world'.

Fisterra enjoys a kind of mythical status as being at the "edge of the world". The name Fisterra comes from Latin 'finis terrae', literally 'end of land'. Mistranslations like 'the end of the earth' or 'the end of the world' contribute to the mythology. Cap Finisterre in Brittany and Landsend in Cornwall are similar 'ends of the world'.

The suggestion of menace carries

on with the naming of the nearby

coast as La Costa da Morte, the

'coast of death'. An explanation of

this name asserts it comes from

the pagan belief that, as the sun

disappeared each day into the

sea, it sank into the land of the dead until the following morning when it rose again into the

land of the living.

An alternative theory asserts more realistically that the name relates to the many shipwrecks

that have occurred along this treacherous rocky stretch of shore.

We based ourselves for a couple of days in the small fishing town of Camariñas to walk and

explore the coast. This little town spreads out from its port where colourful fishing boats are

moored. White and pastel coloured buildings have red tiled roofs, pretty in the soft mist that

often settles on the town. Fishing in the ocean and collection of sea urchins and shellfish on

the tidal flats are the base of the economy. Lace making is also an important cottage industry

here.

We found an agreeable pathway that followed the

coast, traversing green hillsides above the rocky

crags that drop down to pebbly beaches,

occasionally a sandy one. There are lighthouses

along these cliffs but, experiencing the misty

atmosphere, we could well imagine the troubles

of shipping in stormy weather.

Indeed in November 2002 the oil tanker 'Prestige' sank and broke up off this coast, causing a spill that polluted thousands of kilometers of coastline and more than one thousand beaches on the Spanish, French and Portuguese coasts. It also caused enormous harm to the fishing industry.

Indeed in November 2002 the oil tanker 'Prestige' sank and broke up off this coast, causing a spill that polluted thousands of kilometers of coastline and more than one thousand beaches on the Spanish, French and Portuguese coasts. It also caused enormous harm to the fishing industry.

The spill was the largest environmental disaster in the history of both Spain and Portugal and has taken

years to remedy.

As we walked along the coastal pathway we came upon a group of workers engaged in the cleanup. Only now, in 2012, is there some confidence that the cleanup has been successfully completed, but there are still reports of small spills from the wreck.

As testimony to the strong winds, or perhaps to Spain's commitment to renewable energy, there were lines of windmills on every hill. Our walk took us in a loop back to town past an anchovy factory, an aromatic reminder of the local industry. We ate wonderful sea food in Camariñas.

As we walked along the coastal pathway we came upon a group of workers engaged in the cleanup. Only now, in 2012, is there some confidence that the cleanup has been successfully completed, but there are still reports of small spills from the wreck.

As testimony to the strong winds, or perhaps to Spain's commitment to renewable energy, there were lines of windmills on every hill. Our walk took us in a loop back to town past an anchovy factory, an aromatic reminder of the local industry. We ate wonderful sea food in Camariñas.

On either side of the Costa da Morte are the Rias Bajas and

the Rias Altas. The Rias Bajas is a series of beautiful

estuaries that extend down towards the Portuguese border.

There are long distance walking trails through this area and

also many short routes, particularly around the town of Vigo.

In the village is a little granite chapel consecrated to Saint Andrew and, so they

say, keeping his bones. Every year on 8 September it is the focus of a pilgrimage

but throughout the year there are many visitors buying tacky souvenirs from the

many stalls that line the streets.

According to another legend it is said that if "you don't visit San Andrés de Teixido in life will do so in death". Various interpretations of the legend then say

According to another legend it is said that if "you don't visit San Andrés de Teixido in life will do so in death". Various interpretations of the legend then say

At Cape Ortegal the notion of "end of the earth/world"

reappears. According to Tacitus (some say), it is here that

"heavens, seas and earth end", so making it the End of the

World. It certainly seemed so to us as we emerged from the

mist and found ourselves in the little village San Andres de

Teixido.

Around here we started to see the granaries that are

such a feature of Portugal and north west Spain.

Sometimes constructed in stone, sometimes

wooden slats they are perched on granite stilts.

They are called hórreos around here and are

exceptionally photogenic.

To the north east of La Coruña, the Rias Altas take you into

the wild country of Cabo Ortegal where, if you are lucky

enough to have clear weather you would find yourself in a

small corner of heavily wooded forests where the precipitous

rocky coastline drops into the sea. We drove through here in

cloud so deep that the road ahead was invisible, though we

did see the occasional walking track heading off in the mist.

Around Ferrol there are a number of marked tracks, such as

one leading from Ferrol to San Andres de Teixido.

that you will return in the form of

an insect, a serpent or a lizard

and because of this visitors are

very careful not to tread on these

creatures. Some scholars also

suggest that pagan peoples

believed this was the starting

place for the souls of the dead on

their journey to the Other World.

This is a dramatic place, especially when it is bleak and foggy and big seas crash against the rocks at the base of the steep cliffs. It is not hard to understand why all the myths and legends have flourished.

This is a dramatic place, especially when it is bleak and foggy and big seas crash against the rocks at the base of the steep cliffs. It is not hard to understand why all the myths and legends have flourished.

Inland Galicia - the Ribiera Sacra

The owner of a small stylish pension in Castro Caldelas, when

we woke him from his siesta, enquired with some

astonishment how we had found his town. He was happy,

though not entirely satisfied, with the explanation that we

liked quiet, out of the way places and that we planned to

explore the surrounding area and do some walking in the hills

of the Ribiera Sacra.

Castro Caldelas, in the heart of the Ribiera Sacra, is a hidden secret - a mountain top town with a castle and a couple of churches, interesting stately homes emblazoned with coats of arms and a good array of restaurants and bars. The old quarter, above which towers a 14th century castle, is a compact cluster of narrow streets and squares where the houses are often built on the bare rock. Our pension was in the old quarter, nestled under the castle. It ticked all our boxes.

The name Ribera Sacra, or sacred riverbank, comes from the clustering of Romanesque churches and monasteries found round here. The rugged, isolated area attracted hermits and monks who settled here from early Christian times, building the monasteries which became centres of art and culture.

Castro Caldelas, in the heart of the Ribiera Sacra, is a hidden secret - a mountain top town with a castle and a couple of churches, interesting stately homes emblazoned with coats of arms and a good array of restaurants and bars. The old quarter, above which towers a 14th century castle, is a compact cluster of narrow streets and squares where the houses are often built on the bare rock. Our pension was in the old quarter, nestled under the castle. It ticked all our boxes.

The name Ribera Sacra, or sacred riverbank, comes from the clustering of Romanesque churches and monasteries found round here. The rugged, isolated area attracted hermits and monks who settled here from early Christian times, building the monasteries which became centres of art and culture.

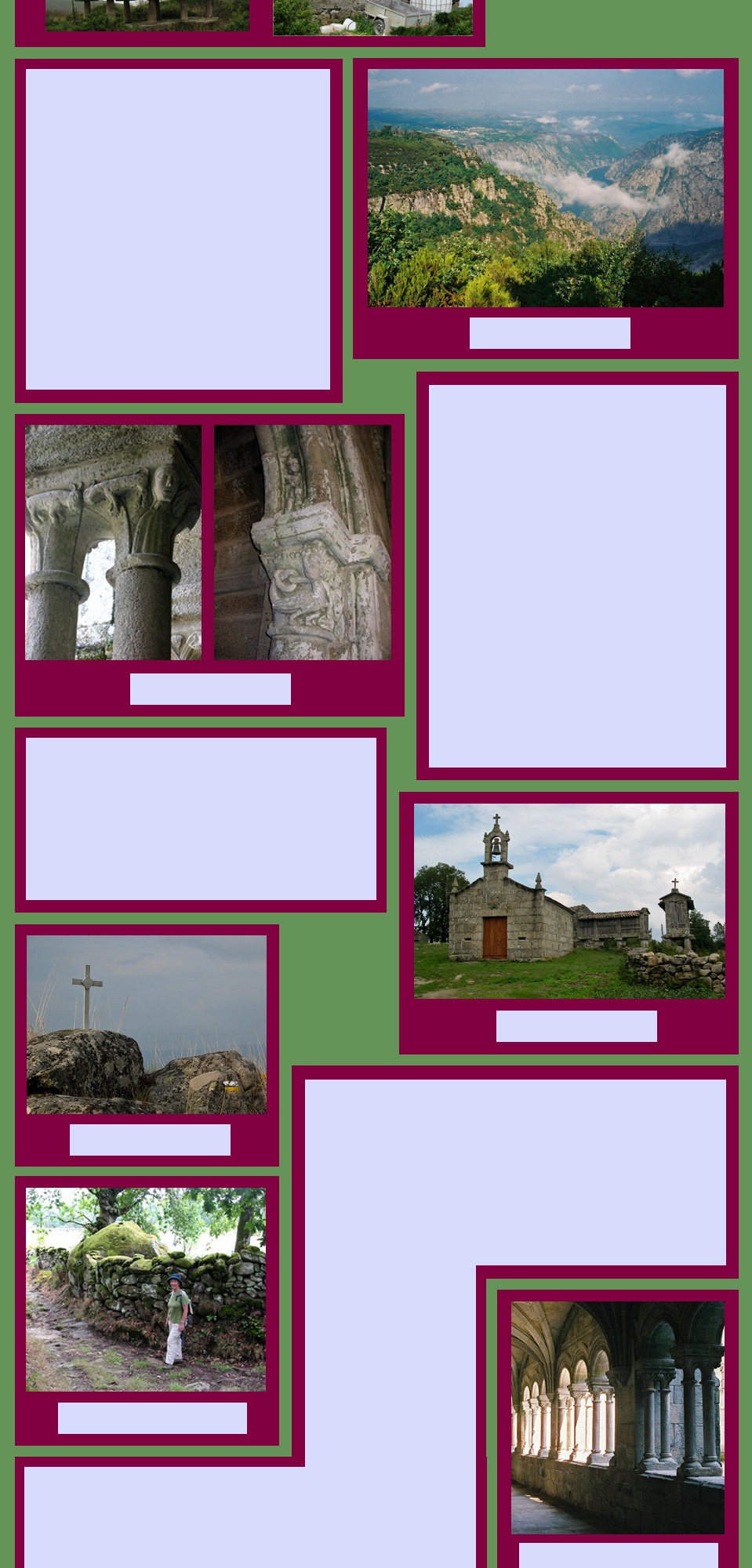

The canyon of the Sil is up to 500 m deep in some places

and along the rim there are numerous natural viewpoints, or

miradors that hang in the sky overlooking the river.

Terraces of vines perch precariously on the improbably steep slopes. Wine production has been carried out here since Roman times when the first terraces were carved out of the rock by slaves. Today wine-making thrives. The combination of native grape varieties, slate and granite soils, and the microclimates of the rivers and their terraces produce excellent growing conditions, for distinctive red wines in particular.

We split our time here visiting some of the monasteries, doing some of the walks in the area and gazing in awe at the view from the miradors. There are some long walks here and many short ones, with good information available from the local tourist office.

Terraces of vines perch precariously on the improbably steep slopes. Wine production has been carried out here since Roman times when the first terraces were carved out of the rock by slaves. Today wine-making thrives. The combination of native grape varieties, slate and granite soils, and the microclimates of the rivers and their terraces produce excellent growing conditions, for distinctive red wines in particular.

We split our time here visiting some of the monasteries, doing some of the walks in the area and gazing in awe at the view from the miradors. There are some long walks here and many short ones, with good information available from the local tourist office.

The river is the Sil which rises in the Cantabrian mountains

and flows to join the river Miño which then goes on to form

the border between Galicia and Portugal. The geography

here is comprised of high plateaus and mountains with

gentle slopes that give way abruptly to the waters of the Sil.

This is some of the most spectacular gorge scenery in Europe. While the canyons of both the Sil and the Miño are impressive, those of the Sil are steeper, rockier and more inaccessible than the greener, gentler banks of the Miño, which have lent themselves more to human habitation.

This is some of the most spectacular gorge scenery in Europe. While the canyons of both the Sil and the Miño are impressive, those of the Sil are steeper, rockier and more inaccessible than the greener, gentler banks of the Miño, which have lent themselves more to human habitation.

Narrow pathways run between stone walls covered in moss and pass

through villages of stone houses around which cluster the granaries that

are so characteristic of the area. The villages are very neat and well

maintained and the granaries are obviously all very much in use.

Sometimes there is a little church at the centre of the village and

sometimes there will be a cross, a cruciero, to mark the way or provide

inspiration.

It is delightful, easy walking with the occasional frustration of the way markings disappearing but after a while the trusty yellow and white signs reappear and walking instructions, maps and the lay of the land all line up again. Only a minor frustration really.

It is delightful, easy walking with the occasional frustration of the way markings disappearing but after a while the trusty yellow and white signs reappear and walking instructions, maps and the lay of the land all line up again. Only a minor frustration really.

Of the monasteries in the area we visited two - San Esteban de Ribas de Sil and San

Pedro de Rocas.

San Esteban de Ribas de Sil, located to the north of the village of Nogueira de Ramuín is now a state-run Parador, and is reputed to be the largest and one of the best examples of Romanesque Galician architecture. Its setting alone, with spectacular views down to the river make it worth a visit.

References to the monastery's existence can found as far back as the 10th Century, although its origins appear to date back even further, to the 6th and 7th centuries. Inside, various styles can be seen from Romanesque to Baroque, and its three cloisters, all from different periods, are lovely peaceful places. Also of note is its Baroque façade which was added in the 18th Century. The building was declared a historic artistic monument in 1923.

San Esteban de Ribas de Sil, located to the north of the village of Nogueira de Ramuín is now a state-run Parador, and is reputed to be the largest and one of the best examples of Romanesque Galician architecture. Its setting alone, with spectacular views down to the river make it worth a visit.

References to the monastery's existence can found as far back as the 10th Century, although its origins appear to date back even further, to the 6th and 7th centuries. Inside, various styles can be seen from Romanesque to Baroque, and its three cloisters, all from different periods, are lovely peaceful places. Also of note is its Baroque façade which was added in the 18th Century. The building was declared a historic artistic monument in 1923.

After a twisty drive down a

narrow country road we found

Mosteiro de San Pedro de

Rocas (Monastery of Saint

Peter of the Rock). Although

entry is not allowed into the

Monastery itself, the attraction

here is the church, carved into

the rocks of the mountain hence

the name "of the Rock". It is

believed to be the first hermit

settlement in Galicia, the

presence of the earliest

inhabitants being traced back to

the year 573.

According to the inscriptions on its foundation tablet, which is kept at the Provincial

Archaeological Museum, its founders were seven men who chose this beautiful spot as a

retreat to lead a life of prayer.

We loved this quiet area which seemed

so peaceful and calm. So it was with

terror and alarm that we were blasted

awake one night at 2.30 am by

explosions and flashing bursts of

light.They seemed to be right above, or

even inside, our little pension. After a

few bewildering seconds we realised

that fireworks were being set off from

the castle which was indeed right above

us. A local fiesta, we discovered, which

carried on nearly till dawn.

to Top of Page

Galicia

This simple chapel is small, as churches go, and the rock walls are rough hewn, not smooth

and finished. There were no seats but there were burial places carved into the floor. They are

empty now and slowly wearing away. The place was declared a Historical Artistic Monument

in 1923.

From the Ribiera Sacra our

journey continued into the

Cordillera Cantabrica

and

Los Picos de Europa.

journey continued into the

Cordillera Cantabrica

and

Los Picos de Europa.

Spider sculpture, Guggenheim

Bilbao

Bilbao

Cabo Ortegal

Cathedral at Santiago

de Compostella

de Compostella

At the end of the journey

Cabo Ortegal

Cleaning the Costa da Morte

Sant Andrés de Teixido

Coastline at Sant Andrés de Teixido

Cariño on Cabo Ortegal

Cañon de Sil

Ornamentation

San Estevo de Ribas de Sil

San Estevo de Ribas de Sil

Village church near Castro

Caldelas

Marking the way

Walking on the Rota Noguira-Linares

Cloister, San Estevo de Ribas de Sil

San Estevo de Ribas de Sil

San Pedro de Rocas

Visit FRANCE

Visit ITALY

More of SPAIN/PORTUGAL

Explore on MAPS

Return to HOME PAGE

Explore PHOTO GALLERIES

View pictures of